Colliding Christianities at #Justice2015

07-17-2015

By Student Ryan Kenji Kuramitsu

I walked into the Justice Conference with insects flittering around in my gut. While I would have been pining to go to an event like this in my evangelical days, my very understanding of justice (and how it should be implemented) has shifted in recent years, from carceral to conciliatory, from retributive to rehabilitative. Further overloading my anxiety about attending the event was the fact that the spiritual abuse I have endured at the hands of former friends and mentors still orients my heart towards fear whenever I am around people who remind me of the people who hurt me (read: white, “Bible-believing,” Jesus-loving evangelicals).

Only in recent years, looking from the outside in, have I learned how the justice of white evangelical philanthropic sensibilities is often framed in damaging paternalistic or colonialist terms – we are saved, good, okay, and those people, there, in Africa, or Mexico maybe, need us to rescue, uplift, save, help them. Those poor women and children are trapped and need Jesus (and a Christian man to head their home) and only we can go into those places and bring the gospel there so that they can be saved.

This is the brand of “justice” I expected to find in Chicago’s Auditorium Theater this past weekend, surrounded by 2,500 well-meaning people who would make me deeply uncomfortable without realizing it. In short, I was afraid this weekend would fill me with more white-centric, anti-intellectual, or spiritually coercive teachings couched in friendly evangelical language – perhaps channeled through a few colored bodies. I have been to perhaps dozens of conferences similar to this one, both conservative and progressive in scope, where I have sat silently and attempted to glean grains of truth from a message I knew wasn’t designed for people like me.

However, I attended at the invitation of my friend Micky, who was kind enough to offer me a ticket. Upon arrival, I was surprised that I recognized several people, both on stage and in the audience. These were folks I called friends, and they didn’t remind me of my abusive experiences with Christianity at all.

Right off the bat, I saw the pre-conference “race and reconciliation” track featured some of the most prophetic and incisive voices on the scene today, folks who teach, preach, and compose the forefront of race and reconciliation thinkers in the church and academy. We heard (my future seminary professor!) Christian ethicist Reggie Williams lecture on the pervasiveness of white supremacy, Harlem renaissance resistance theology and art, and the history of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s black Christ. The inimitable Andrea Smith spoke only on a short “women of color panel” with seasoned faith leaders Kathy Khang, Chanequa Walker Barnes, Micky Jones, and Sandra Van Opstal.

All of these women – some of whom have unmatched academic credentials and are already extremely well known – would have more than commanded the crowd at a main stage session, but were not given that opportunity. Indeed, many of their names weren’t even listed on the website or any conference materials. Though they didn’t have more stage time, many continued to prophesy via tweets throughout the weekend.

Some of my friends who couldn’t attend tried to learn about the conference through Twitter, where many live-tweeted quotes and updates. The Justice Conference’s sparse website doesn’t offer much at all in the way of information on speakers, schedules, or content, and it didn’t seem like the conference wrought much external media coverage. Nonetheless, the event is a yearly staple for those in justice-seeking evangelical traditions, and it is important because it has the ability to influence thousands of faith leaders to set long-lasting social trends.

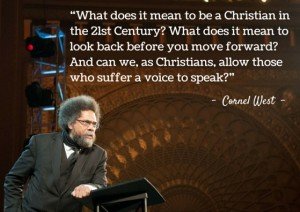

Though most of the thin online coverage was positive and accurate, there were a few individuals who seemed to miss the point. Twitter trolls balked at the conference’s engagement of race, calling the content that filled the #Justice15 hashtag “White-genocide type tweets.” Disapproving journalists (who we’ve met before) reported on the “controversy” of some of the main stage’s African American speakers (Cornel West, Otis Moss III, by extension Neichelle Guidry Jones) by fielding the alarmed reactions of several ruffled social economic conservatives (who happened to be Christian).

Some voiced frustration that Lynn Hybels was allowed to speak on peace in the Middle East because the co-founder of Willow Creek Community church “has sometimes criticized Israel.” A professor at a nondescript Christian College in the Midwest complained that “progressive thinkers rarely focus on job creation” and lamented “the myth of socialism.” Another critic condemned the conference’s liberation theological influence because “entitlement programs and wealth redistribution” don’t work, and neither does trying to create a “socialist utopia.”

We heard biblical, Christian perspectives on the impact of white supremacy on the survival of people of color – talks about police brutality, the spiritual consequences for worshipping a white Christ, prophetically confronting structural and systematic systems of oppression, the patriarchal exclusion of women from the pulpit, histories of American racism, racial profiling (too real, happened in full right after the conference) and mass incarceration – and Soong-Chan Rah boldly called out white colonizers who think they’re being missionaries.

I have a hard time seeing what any of these veiled, derailing economic platitudes have to do with orthodox/unorthodox theology. That these folks are attempting to malign or debunk liberation theology not on ethical, biblical, or theological grounds, but because capitalism is best – is very telling. Indeed, as Justice Conference speaker Soong-Chan Rah has noted on the article, “the attempt to engage liberation theology is not on theological merits. Instead, it appears to rehash social economic conservatism couched in ‘evangelical’ language.”

Despite my initial concerns, it seemed like the audience at the Justice Conference boasted a lot of people like me – Christians who love Jesus, believe in the Holy Scriptures, seek justice, and who have sometimes chafed greatly under traditional evangelical strictures. To us, the “controversial” speakers like Cornel West didn’t feel out of place nearly as much as the starchy, unexceptional talks given by folks like Louie Giglio.

In the midst of a conference specifically mired in critical conversations about how Christ followers should interact with others in a world gripped with poverty and racism, Giglio addressed neither, instead touching briefly upon the issue of human trafficking (through a gimmicky introductory video that cited vastly overblown, inaccurate figures) then focused on describing God’s peacemaking deal with us, and why we should generally care about being just.

It didn’t go unnoticed that Giglio’s pleasant but ordinary talk was far from representative of the witness of the conference as a whole. Rather, his message, by not acknowledging the key racial and systemic factors organizers seemed to focus on, seemed to add mainly to the whiteness of the conference.

The truly refreshing thing to me – as a multiethnic Nikkei, as a person of color, as a full supporter of the inclusion and headship of LGBTQ people in the church, and as someone whose moral fiber and Christian practice has been deeply weakened by the male-dominated theological environments in which I continue to be formed – the really hopeful thing about #Justice15 was that the standard-slate, big name talks given by folks like Louie Giglio (buttressed by presumed commitments to patriarchy and strict biblicism) were the outliers.

Indeed, spoken word artist Malcolm London opened the conference’s main session defending the dignity of transgender black women, lauding queer black men, mentioning by name Marissa Alexander and crucial Chicagoan activists like Mariame Kaba. Throughout the weekend, the main stage bristled with panels and lectures on the concrete social ills still disparately experienced by people of color in the United States.

We heard biblical, Christian perspectives on the impact of white supremacy on the survival of people of color – talks about police brutality, the spiritual consequences for worshipping a white Christ, prophetically confronting structural and systematic systems of oppression, the patriarchal exclusion of women from the pulpit, histories of American racism, racial profiling (too real, happened in full right after the conference) and mass incarceration – and Soong-Chan Rah boldly called out white colonizers who think they’re being missionaries. There were also moments of levity and joy, jokes and laughter that pierced the room at unexpected, life-giving moments.

While there is one Justice Conference, there were two fairly distinct Christianities represented. They met in a finely orchestrated clash of creativity and force, and it was fascinating to watch cutting-edge Asian American and black liberation theologies collide with the monochromatic, male-centric, miles-wide-inches-deep Western evangelical theology that we so often just call “theology.”

The murky boundaries of evangelical “orthodoxy” are hotly contested borders, and perhaps because many view the biggest fault lines as being primarily around LGBTQ concerns have such candid conversations on race been able to find a home under the Justice Conference’s broadly evangelical umbrella.

Is Cornel West at home within the camp of white evangelicalism? Is Otis Moss III? Probably not. But with a bit of spiritual gerrymandering, conference organizers were able to find authentic ways to introduce and center these voices, even alongside more conservative, watered-down counterparts.

Refreshingly, this noteworthy collusion often happened without aggression or rancor. #Justice15 welcomed an audience from all places on the spectrum of justice awareness/ engagement, and encouraged all of us to go deeper in faithfulness, with God’s help.

Yet while I appreciated the big tent and denominational diversity of the talks, the dissonant theologies presented from the same stage sometimes caught me off guard. Attendees heard from pre-conference speaker Native theologian Mark Charles on the theft and pillage of indigenous land and the United States’ sinful “doctrine of discovery” – then raised our voices with a praise band asking God to “win this nation back.” We watched powerhouse preachers of color directly challenge us and name white supremacy in the church – then listened to entire messages delivered by white dudes that didn’t think race worth mentioning once.

It was a bit like hearing a series of alternating lectures – one from the Popular White Christian Conference Speaker Dude™ religious equivalent of your third grade arithmetic teacher, then another from an outside-of-evangelicalism faith leader primed on graduate-level spiritual calculus – and then hearing only brief (but brilliant) quotations from women of color professional mathematicians consigned to “women’s panels.” (There was literally a “women’s lunch” and a “pastor’s lunch” on the second day of the conference. Guess how many women were on the panel that spoke at the pastor’s lunch.)

Although the stark language of sinister “powers and principalities” at play in this world often bristles against both conservative emphasis on individual sin and liberal skepticism of the supernatural, this rhetoric is anything but hyperbole. Ask the people of color, the women, the queer and transgender folks in your communities (if you know any). The unjust things in this world are not just here by chance. There are planned, evil, satanic systems alive in the air we breathe that are nothing short of demonic.

The good news is that God has sent us a Helper, an Advocate, to give us life and strength to challenge the wicked systems and powers at work in our world. The liberative Spirit of God breathes fresh life to all in pain, and will always comfort, heal, and bewilder us, even as it continues to challenge our fears, demolishing our preconceptions and blowing around in the most unexpected of auditoriums. I am grateful to have been reminded of this at this year’s Justice Conference.

Student Ryan Kenji Kuramitsu recently completed his Bachelor’s Degree at the University of Illinois and is excited to enter his MDiv education in the fall of 2015. Ryan is a prolific writer, an activitst, and public speaker. You can read more of his reflections on his blog (where this post first appeared), and follow him on twitter @afreshmind